Accessible Travel - San Diego Zoo

I love to travel, especially when it means visiting friends! San Diego is one of those spots, and on this trip I finally had the chance to visit the San Diego Zoo. I’ve always been an animal person — I even thought about becoming a veterinarian when I was a kid — so zoos have always held a special place for me. I was excited to go, and honestly, I was even more impressed by the accessibility features than I expected. If you’re thinking about visiting the Zoo and you have a disability, there are quite a few things in place that make the day easier and a lot more enjoyable.

First off, they have A LOT of accessible parking. The zoo is a popular place, so it was nice to see the amount of parking available. They do have options to rent a manual or electric wheelchair on a first come, first serve basis for a fee. But, in line with the ADA, you can also use your Other Power Driven Mobility Device (OPDMD) —so not just manual chairs or scooters, but more of your adventure style devices. They have specific parameters in their Accessibility Guidebook but its pretty inclusive.

The Zoo is big, and some parts are hilly, so one thing I appreciated is that the map clearly marks an "accessible route” with a blue dotted line through the grounds that allows you to access points while avoiding the steeper hills. There’s also a complimentary ADA shuttle for people with mobility-related disabilities, which helps with some of the longer or tougher sections.

When it comes to personal care, every restroom on the property is marked as accessible, and there’s also an adult changing station located at Health Services near the Reptile House. I do wish there was more than one option as the Health Services building is in the front, and the zoo is pretty giant, but at least there is an option besides the floor. The zoo staff are not allowed to help you in the bathroom, however if you require support from an attendant or caregiver, the Zoo offers a free admission pass for that person. It’s one less cost to worry about and makes the visit more realistic for people who can’t go alone.

They’ve also put real thought into sensory accessibility. If you’re neurodivergent or traveling with someone who is, the Zoo offers sensory bags that include tools like headphones, fidgets, and visual aids. Around the busier or noisier areas, you’ll find signs letting you know when those tools might be especially helpful. They also have weighted lap pads and an app with social stories to best prepare people for their zoo experience. These are small things that can make a big difference in how the day feels.

Personally, I got a bit overstimulated. It wasn’t all that busy, but I still had a hard time regulating. Seeing the sensory options made me consider getting my own Loop earplugs for things such as this. So many of us ignore those signs of distress simply because we don’t consider it a “disability” but these support services can be helpful for a lot of people.

Overall, the Zoo has done a great job of creating a space where people with different access needs can move around, enjoy the animals, and focus on the experience instead of the barriers. It’s not perfect—no place is—but the information they provide helps you plan ahead and avoid surprises.

My favorite part of the zoo was seeing the otters because they were SO active and playing around. Our 5 year old goddaughter really loved how much they darted back and forth in the water, swimming with glee. But close second was the Aerial Tram. I love being high up, and it offered beautiful views of the tree canopies and some of the animals from above. The tram is accessible if you have a folding wheelchair AND can transfer to the regular gondola seat, but otherwise it is not. I would love to see more opportunities for all visitors to access this, because it is truly breathtaking.

If you’re thinking about visiting the San Diego Zoo, I’d recommend checking out their accessibility guide before you go, deciding whether you want to follow the easiest route, and planning for the hills if they affect your energy or mobility. With a little preparation, the Zoo can be a fun and manageable day out.

Accessible Trails, Inclusive Programs: Why Your Organization Needs Both

Outdoor recreation is more than a perk—it’s a key component of health, community connection, and belonging. Yet far too many trails, parks, and programs leave people with disabilities on the sidelines—because the barriers are built into the system. That’s where I come in.

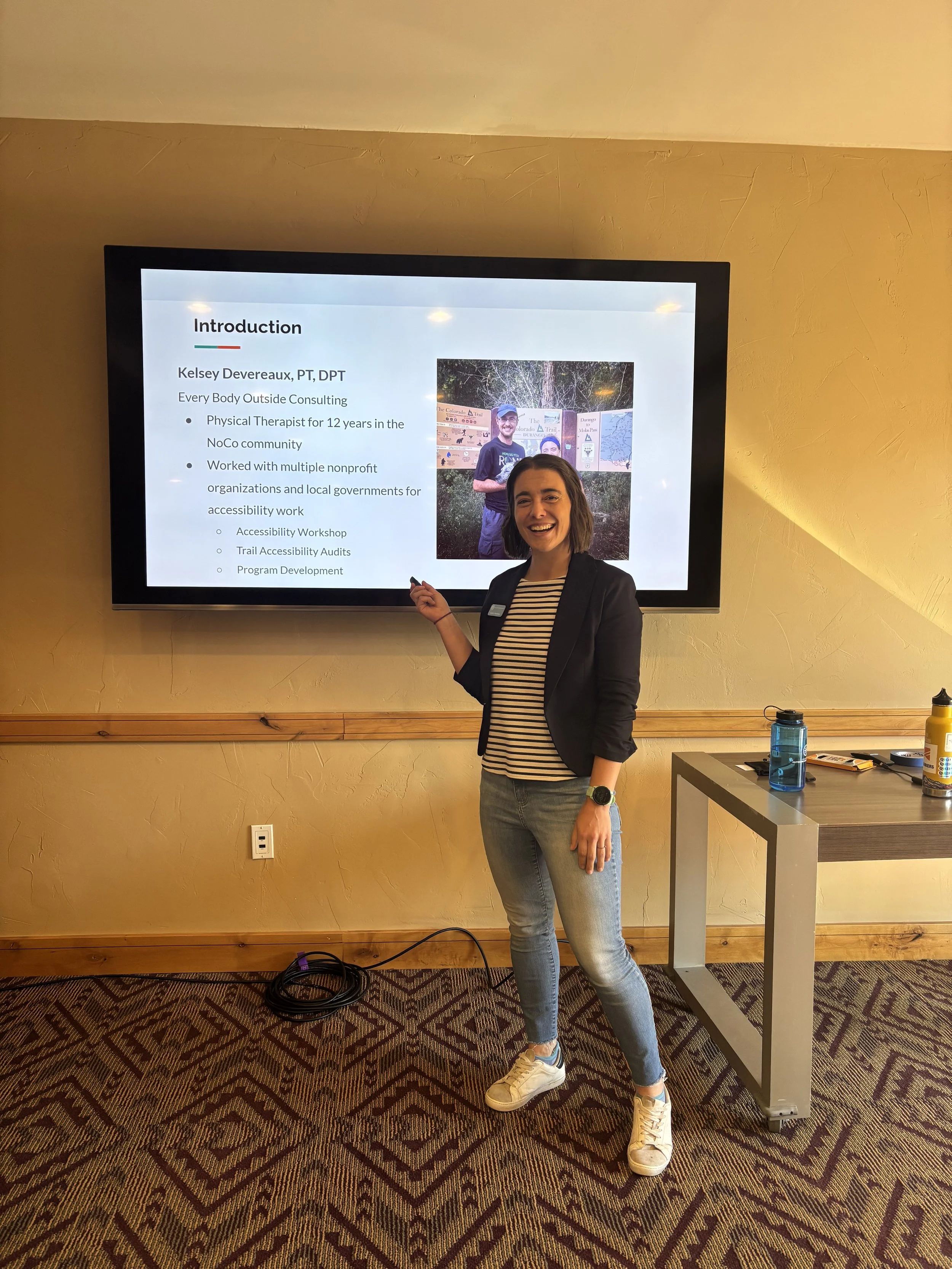

With over a decade of experience as a physical therapist plus deep engagement in adaptive recreation (for example, for adults with disabilities through organizations like No Barriers USA and Cycling Without Age), I founded Every Body Outside Consulting to support land managers, nonprofits, and outdoor-recreation providers in shifting away from “compliance only” toward meaningful, inclusive design and programming.

Here’s what I can bring to your organization:

1. Education & Training

Whether it’s a half-day workshop or a leadership session, I deliver education sessions tailored to your team’s roles. These go beyond the basics of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) to explore what accessibility really means in outdoor settings—online registration, trailhead access, gear, transportation, signage and more. As one client shared:

“The training was so well received… our staff members left the training inspired to approach their responsibilities with an accessibility-focused mindset.” — Julie Enderby, Larimer County Department of Natural Resources.

2. Program Development for All Abilities

Don’t just bolt on inclusion—build it in. I help you design or refine your programs so that people with mobility, sensory or cognitive disabilities are considered from the start. We cover everything from participant recruitment, adaptive-equipment strategy, emergency action planning, and partnerships with disability-led or inclusive organizations. One testimonial:

“Kelsey has helped No Barriers identify how to better support people affected by disabilities in the Fort Collins and greater Colorado community.” — Emily Bastos, Program Director, No Barriers.

3. Trail & Facility Audits

A trail looks accessible until someone with a mobility device tries it. I use a trail audit tool developed with people with disabilities in Northern Colorado to assess your existing trails, picnic areas, restrooms, parking, route signage, and more. We identify barriers, suggest practical improvements, and translate them into actionable plans aligned with your values and strategic goals. We have done this from the Purgatoire Watershed Partnership down in Trinidad to the City of Greeley Natural Areas.

Why This Matters — And Why Now

Broader impact: Accessible trails and programs serve not only people with disabilities, but older adults, families with strollers, and anyone recovering from injury. Investing here means reaching more people.

Reputation and mission alignment: Your organization has a stake in inclusion, equity, and serving community. Being intentional about accessibility sends a strong signal: “Everyone belongs here.”

Risk mitigation and smart investment: Rather than waiting for a barrier complaint or retrofit scramble, a proactive audit and training ensures you’re ahead of evolving expectations and inclusive practice.

Culture change: Accessibility isn’t just a checkbox—it’s about how your organization thinks, plans and operates. Training and development reinforce that shift.

If You’re Ready for Next Steps

Over the coming year I have a few openings for new partnerships. Whether you’re planning a new trail segment, revisiting your outdoor program strategy, or simply looking to build an inclusive culture in your organization—let’s talk. I’ll work with you to define scope, align with your budget and timeline, and tailor the approach that fits your team.

Send me a message or schedule a quick call. Together, we’ll create outdoor spaces and programs where every body can participate, thrive, and enjoy.

#OutdoorAccessibility #TrailAudit #InclusivePrograms #UniversalDesign #EveryBodyOutside

Finding Freedom Outside: Outdoor Opportunities for the Blind and Visually Impaired in Colorado

Getting outside means something different to everyone. For folks who are blind or have low vision, it can be about independence, trust, and connection — not just with nature, but with the people who make it possible to experience it fully. Here in Colorado, that can look like scaling a cliff with a trusted belayer, using technology to explore a new park, or following a rope along a quiet forest trail.

Adaptive Adventures and Paradox Sports have been doing this work for years — creating spaces where blind and visually impaired climbers can show up, learn, and climb on their own terms. Adaptive Adventures keeps things approachable with clinics and community climbs across the Front Range. I have volunteered for this organization over the years in my home town of Fort Collins where they run climbing nights once a month at Whetstone and Ascent Climbing Gym. Paradox Sports, based in Boulder, builds community through trips and local sessions that mix new climbers, seasoned athletes, and volunteers into one supportive crew. These groups are living proof that outdoor recreation isn’t about ability — it’s about belonging.

photo credit from Colorado Outdoors

The Colorado Center for the Blind has been out there too, literally. Colorado Parks & Wildlife recently helped fund their climbing program, and the story “Reaching New Peaks” in Colorado Outdoors captured one participant’s experience perfectly: “I want people to know that we are just like everyone. Blind people also want to spend time outside. Climb rocks, white river rafting, go to the beach. Heck yeah, let’s do it all. Let’s go surfing!” That quote says it all. The bottom line is we all crave the same thing — freedom and connection in the outdoors.

Cycling is another way people are getting outside together. EyeCycle Colorado pairs blind and visually impaired riders with sighted captains on tandem bikes for group rides all across the Front Range. Their outings range from casual neighborhood spins to long weekend routes, and every ride builds trust and community. It’s not about speed or competition — it’s about movement, freedom, and the shared joy of being on the road with others who get it. They got a ride for New Years Day so there are still opportunities to get out there!

Photo Credit from Boulder Open Space and Mountain Parks

Colorado Parks & Wildlife has also made it easier for blind and low-vision visitors to explore parks independently through Aira, a smartphone-based service that connects users with trained visual interpreters. Aira agents can describe what’s around you, help with directions, or read interpretive signs — all in real time. One user put it simply: the program lets people “explore their neighborhoods, their worlds” with more confidence. It’s small tech with a big impact.

And for those who prefer to move at their own pace, Colorado has some truly special accessible trails. The Braille/Discovery Trail near Aspen has tactile guide ropes and Braille signs that make it easy to explore on your own. Down near Colorado Springs, the VIP Trail at Bear Creek Nature Center offers similar features — rope guides, tactile signs, and smooth surfaces. And in Boulder, the Sensory Trail winds through pine forest and wildflowers, encouraging visitors to notice the smells, sounds, and textures that most of us usually overlook.

photo credit from Eyecycle Colorado

All of these options — from adaptive climbing to sensory trails — show what’s possible when access is built into the design instead of added as an afterthought. Getting outside isn’t about checking a box or overcoming something. It’s about choice, joy, and connection.

So whether you’re clipping into a harness for the first time or just taking a walk to feel the sun and wind, know this: the outdoors belongs to you, too.

If there are specific areas you enjoy that I missed, please let us know so we can share them with the community!

Using Disability as a Cover to Undermine Conservation

And here we go again — another attempt to use “disability access” as a cover to roll back conservation protections.

Senator Mike Lee and Representative John Curtis recently introduced the so-called Outdoor Americans with Disabilities Act. At first glance, it sounds like something worth celebrating. Who wouldn’t want to see more opportunities for people with disabilities to access public lands? The name suggests improvements like accessible water access at reservoirs, better adherence to Forest Service Outdoor Recreation Guidelines, or expanded access for Other Power-Driven Mobility Devices (OPDMDs) like adaptive bikes and Class 2 e-bikes.

But once you dig in, the reality looks very different.

This bill isn’t about increasing access. It’s about building more roads and bypassing the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), all under the guise of helping people with disabilities “drive farther” into protected areas. In short, it uses the language of disability inclusion to push an anti-conservation agenda.

There’s a long and troubling history of this kind of maneuvering — where the idea of “helping” people with disabilities is used as a shield to justify weakening public land protections. In my work, I’ve seen firsthand how this narrative is weaponized. The assumption is that if a policy claims to improve access, it must be good for the disability community. But accessibility and conservation are not opposites. In fact, they depend on each other.

Accessible trails, adaptive recreation programs, and inclusive outdoor spaces thrive in healthy, well-managed ecosystems. Destroying fragile landscapes in the name of access doesn’t create inclusion — it undermines it. It sends the message that the only way people with disabilities can experience nature is by driving over it, rather than engaging with it meaningfully and sustainably.

Yes, a few organizations that specialize in off-highway vehicle (OHV) recreation for people with disabilities have voiced support for this bill. But they do not represent the broader disability or conservation communities, both of which have made their opposition clear. Most of us recognize that this legislation doesn’t address the real barriers to outdoor access: inaccessible infrastructure, poor implementation of accessibility guidelines, and lack of funding for adaptive recreation programs.

As Anneka Williams from Winter Wildlands Alliance put it, “The proposed bill uses adaptive recreation as a scapegoat to further advance an agenda that favors development and unsustainable use of our public lands.” That statement captures the issue perfectly. This is not about disability rights. It’s about dismantling environmental safeguards — and using our community as a convenient excuse.

If lawmakers truly wanted to make outdoor spaces more inclusive, they could start by investing in what actually works. Fund trailhead redesigns that meet accessibility standards. Support adaptive recreation programs that already partner with the Forest Service and local parks. Expand training for land managers on implementing the U.S. Access Board’s Outdoor Guidelines. Those are tangible actions that create real, lasting access.

Accessibility and conservation should always work hand in hand — not against each other. People with disabilities deserve genuine inclusion in outdoor spaces, not to be used as political cover for policies that threaten the very places we’re fighting to protect.

Let’s call this bill what it is: a step backward for both disability access and conservation.

No One Left On Shore

There’s something special about being near water. Many people talk about how calming it is to hear a river flowing or waves crashing against the shore. At the same time, water is powerful — with strong currents and waves that demand respect. That mix of peace and power is what draws us to it.

But for people with disabilities, that experience can slip away. My friend Jim often tells me he misses the simple act of putting his toes in the river, feeling the cold water wash over his feet. These days, his wheelchair can’t make it over the rocks, and even if he got close, transferring out of his chair would be almost impossible.

We all want to see, touch, and hear the water when we spend time outside. The real question is: how do we make sure that experience is possible for everyone?

Why Access is So Hard

Most lakes and rivers are designed for people on foot. Access points often include:

Stairs or steep banks that wheelchairs can’t navigate.

Soft sand, loose gravel, or uneven rocks that make mobility devices unstable.

Changing water levels, especially on rivers, where yesterday’s easy path may be dangerous today.

Equipment Challenges, Many adaptive devices aren’t waterproof, and if they get wet it can damage equipment that’s essential for daily life.

EZ dock Kayak Transfer system (photo credit from EZ Dock)

Adaptive Gear Meets Real-World Barriers

So what is there to do? One option is to rely on adaptive equipment designed for the water.

Beach wheelchairs have large wheels designed for rolling on sand and often can go straight into the water for those who want to swim/float.

Mobi-Mats are firm roll up walkways designed to go on sand or uneven surfaces that can allow wheelchairs, strollers, etc access to the water.

Dock design is essential for making it easier to get on and off watercraft. Thankfully, there are several options that help paddlers of all abilities get into a kayak. One of the most impressive is the EZ Dock system, which combines a loading station, slideboard, and handrails for safe transfers. With this system, the paddler slides onto a transfer board positioned above the kayak seat. Adjustable handles help relieve pressure, the board is removed, and the paddler can safely lower into the kayak.

A similar option is a kayak transfer bench. This bench isn’t permanently attached to the dock and doesn’t include a loading system, so it may require extra equipment and has less universal design. Finally, some docks have tiered benches that allow paddlers to move down step by step until they reach the kayak’s level.

Specialized Equipment like adaptive kayaks with stability features and/or paddle devices allow for more people to get back out on the water. There are also many adaptions for fishing gear for one-handed users and/or different release devices.

River access is especially challenging for many municipalities. Changing water levels and rocky banks make a one-size-fits-all solution impossible. Some of the best approaches I’ve seen include avoiding steps at access points, creating firm surfaces at kayak entry areas, and installing floating or adjustable docks with accessible fishing spots.”

Of course the purchase of this style of equipment is not covered by insurance and would be an out of pocket expense. Many land managers are working toward easing that burden by having equipment available for rent at the location. For instance, Ridgeway State Park has a beach chair and Mobi Mat available for people with disabilities to access their swimming area. They also have adaptive paddle boards available for those interested in exploring a new way to get on the water.

Photo credit from Adaptive Adventures

Programs Leading the Way

Several organizations are already making water recreation possible for more people:

Outdoor Buddies: This is a Fort Collins nonprofit I have talked about before. They specialize in adaptive hunting and fishing, and love to get whole families involved. No matter what difficulties you have, they know how to get you on the water. If you are interested in learning more you could always attend their family days at swift ponds on the Colorado Youth Outdoors campus in east Fort Collins. They even have a floating dock designed to have the immersive experience of fly fishing on campus!

Adaptive Adventures: This organization is based out of Denver and hosts a lot of its programs at Standley Lake and Chatfield Reservoir. If you attend their multisport days you can try out different kayaks and/or stand up paddleboards to see what works best for you. They have a variety of equipment available and have extensive experience working with people of all disabilities.

Fort Collins Adaptive Recreation: Check out your local Parks and Rec departments as they often have programs for adaptive kayaking. The City of Fort Collins partners with organizations like Adaptive Adventures to get their community out on the Reservoir. It is a great chance to try these things out and see what works for you, often at a discounted price.

Closing the Gap

Water has a way of bringing people peace, joy, and connection. Access shouldn’t end at the shoreline. With better design, adaptive equipment, and welcoming programs, we can ensure people with disabilities don’t just watch from the sidelines — they get to be in the water, where they belong.

Take a Seat: What Makes a Bench Accessible (and Actually Enjoyable to Use)

Let’s be honest—sometimes a bench is more than just a bench. On a trail, it’s a sigh of relief, a place to take in the view, or a moment to share snacks with your hiking buddy. But if benches aren’t thoughtfully placed or designed, they can leave out a lot of people who could really use them. That’s where accessibility comes in, and yes, even benches have rules.

According to the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and the Forest Service’s Outdoor Recreation Accessibility Guidelines (FSORAG), benches aren’t just “plop it wherever” pieces of furniture. They’re part of the bigger picture of making the outdoors welcoming to everyone. So let’s break down what makes an accessible bench actually work.

This bench has a nice backrest and is easy to access of the trail, however it does not have a wheelchair spot on the side and has no armrests

Spacing: How Far Apart Should Benches Be?

We all know the feeling of wondering “Are we there yet?” after a steep climb. Best practice is to place benches every 200 to 300 feet on steep or challenging trails, and every 1,000 feet or so on easier terrain. That may sound like a lot, but remember: not everyone is zipping up the trail like a mountain goat. Frequent benches give people with mobility challenges, older adults, and families a chance to rest without turning the hike into a survival test.

The Style That Works Best

Not all benches are created equal. Those fancy, artsy benches that look like modern sculptures? Beautiful in a park downtown, but not so practical on a trail. Out here, we want:

Backrests and armrests – because sometimes you need a little help standing up again. I wouldn’t recommend armrests on both sides however because getting on the bench can be more challenging for a wheelchair user with the armrest in the way. Therefore I recommend only one armrest on a side or the middle of the bench.

Comfortable seat height – about 17 to 19 inches off the ground works for most people. Too low, and you’re doing an accidental leg workout. Too high, and your feet dangle like a kid’s.

Smooth Edges – think weather-resistant wood that is heat resistant with rounded corners. Nobody wants a splinter, large gash on their leg, or a burn when trying to relax and watch the sunset.

Easy to Access - make sure that the benches have an access path that is wide enough for an assistive device (at least 3’ wide) and the drop off from the trail to the access route is smooth.

This bench needs some maintenance as the wheelchair spot has erosion damage and is now a hill that can not be used.

Flat Space Matters

This one is huge: next to every bench, there should be a flat, firm spot where a wheelchair can pull up. That way, a wheelchair user doesn’t have to sit awkwardly behind the bench or in the weeds while their family relaxes. It creates real togetherness—everyone gets to sit side by side and enjoy the break.

Location, Location, Location

Benches should be more than pit stops. Place them in interesting spots—overlooks, shady groves, near water, or by interpretive signs. Shade is also key. Many people with disabilities have difficulty with temperature regulation, and therefore rests in the sun will not work for them. A bench in full sun on a hot day becomes less of a rest stop and more of a frying pan.

Why It Matters

When benches are thoughtfully designed and placed, they turn trails into more welcoming spaces. They send the message: “We thought of you, and we want you here.” That’s what accessibility really is—it’s not about checking a box, it’s about making sure everyone can enjoy the outdoors at their own pace.

So the next time you take a break on a trail bench, notice the details: the backrest, the shade, the view. If all those things are there, someone did their homework—and hikers of all abilities will thank them.

Staunton State Park - Year 2 Reflections

Once again, I found myself early on a crisp August morning staring up at the epic rock formations of Staunton State Park. I was back for the Third Annual Adaptive Recreation Days, hosted by Colorado Parks and Wildlife—and it was awesome.

Last year, I came mostly as a volunteer. This year, I took a new leap and set up my own booth. My goal? Share resources and services available in Colorado for people with disabilities—because one thing I hear all the time is that finding accurate, detailed information about accessible trails and outdoor programs is way harder than it should be.

Sounds simple enough, right? But it was my first event representing my new accessibility consulting business, and there were a lot of little details to figure out. I agonized over T-shirt designs, giveaways, and what activities to offer. Thankfully, my partner Jordan—who works in outdoor events—stepped in with some pro tips. For example, did you know you should bring a chair? I almost didn’t and would have been standing for six hours straight. And my last-minute tent sign? I accidentally ordered it way bigger than I thought. But it looked fantastic, so I’m counting that as a win.

I was lucky to be set up next to Jeremy Siffuentes, Workforce Development and ADA Accessibility Coordinator for Colorado Parks & Wildlife. We hadn’t seen each other since the Partners in the Outdoors Conference, so it was great to catch up. I also reconnected with Kristen Waltz, Track Chair Program Manager at Staunton and the powerhouse organizer behind this event. Her hard work on marketing and advocacy really showed—attendance was noticeably higher than last year.

We also made new friends: Sunrise Medical (off road power wheelchairs), Wilderness on Wheels (accessible camping), Paradox Sports (adaptive climbing), and Greg Sakowicz (aka @fatmanlittletrail) who’s doing great work to get more people outside. Events like this aren’t just for the public—they’re also a powerful way to strengthen partnerships, share new ideas, and keep our passion for accessibility alive. This work thrives when we come together.

From the moment the event started, we were talking with community members, listening to their stories, and gathering input on what “accessible” means in outdoor spaces. The feedback was clear: people want shade, accessible parking and restrooms, adaptive gear on-site, and more immersive experiences—not just a short loop trail. But the biggest theme I heard, over and over, was the need for better access to information about where and how to recreate. People want to know what to expect before they go. We in the outdoor industry can—and must—do a better job of building real connections with the community so our efforts truly meet their needs.

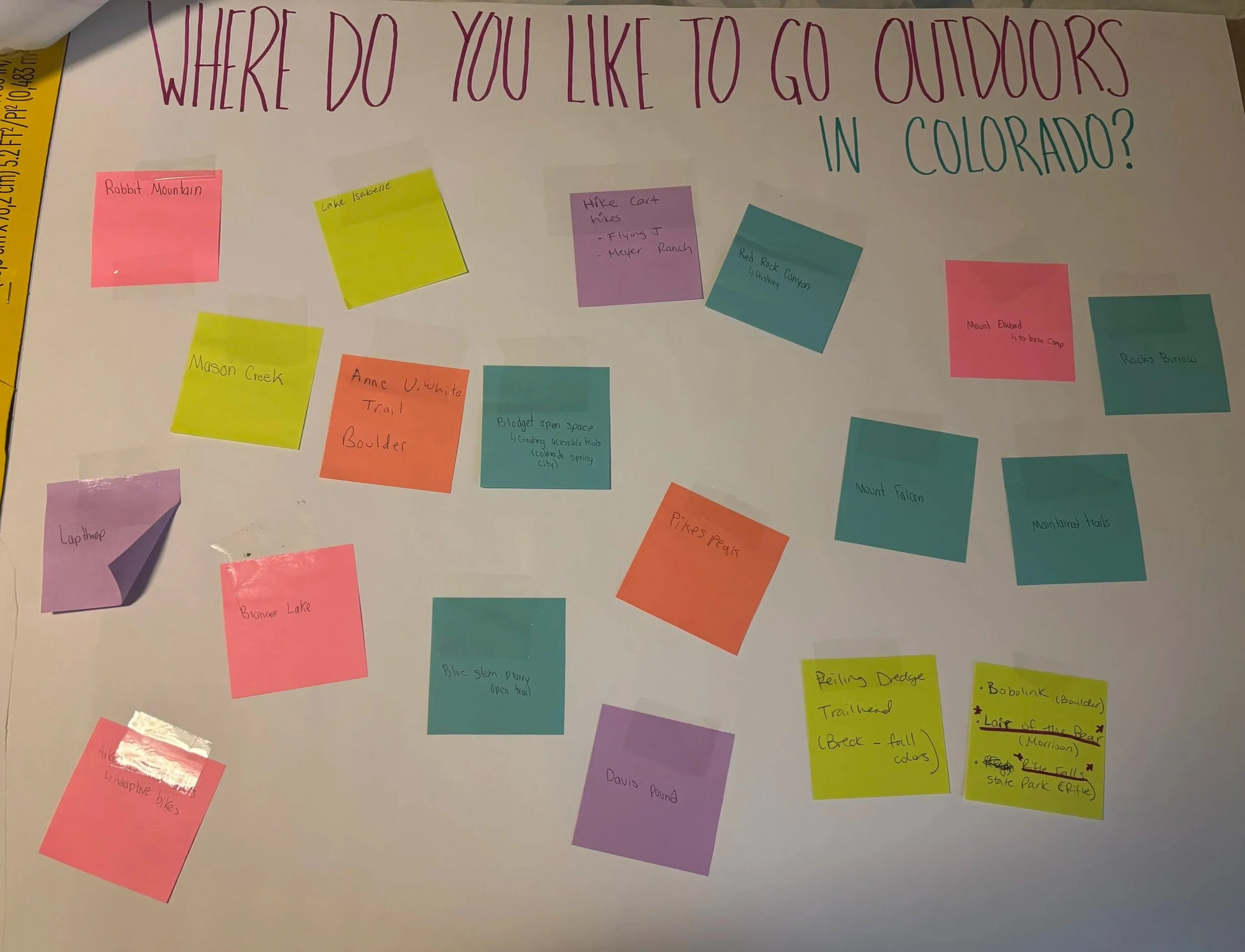

To spark ideas, we had a crowdsourcing board where participants shared their favorite accessible recreation spots in Colorado. Popular mentions included Lair O’ the Bear in Jefferson County Open Space, Arkansas Headwaters for adaptive mountain biking, Reiling Dredge Trailhead in Breckenridge for fall colors, and Blodget Open Space in Colorado Springs.

In return, we shared maps of local state parks with accessible trails marked, introduced people to COTREX and its growing database of accessible trails, and highlighted Boulder OSMP’s accessible opportunities. By the end of the day, we’d swapped dozens of new ideas, resources, and connections.

I’m so grateful I was welcomed back this year in a more prominent role. As an accessibility consultant, I see my role as being an ambassador—helping connect the outdoor recreation community to the people who most need those connections. This event was a perfect opportunity to do exactly that. If you care about accessibility or simply want to explore adaptive outdoor activities in Colorado, I can’t recommend this event enough. Staunton State Park is stunning, the variety of programs is inspiring, and the people you meet will leave you feeling energized and hopeful. I can’t wait to see what next year brings—and I hope to see you there.

Rolland Moore Is Getting a Makeover (and We Need Your Input)

Rolland Moore Park has always been part of my time in Fort Collins.

When we first moved here, we lived just across the bridge and used the park multiple times a week. Even after moving, we kept coming back—to run, bike, play tennis, or just read a book on a shaded bench. I really love this park, and I’m so excited that it’s finally getting some much-needed upgrades.

Under the 2022 Parks Infrastructure Replacement Program Plan, both the tennis complex and playground at Rolland Moore were identified as outdated and in need of serious improvements. Now, with funding from the 2050 Tax Initiative—approved by Fort Collins voters in 2023—the City is kicking off its first major renovation project under this initiative right here at my “OG” park.

Let’s take a look at what’s planned—and where we still need to speak up.

Photo Credit City of Fort Collins with Design Plan for Tennis Complex

🎾 Tennis Complex

The proposed plans include replacing the old asphalt courts with post-tension concrete surfaces, which last over 30 years with minimal maintenance—a smart, long-term investment. Based on community feedback, improvements will include better court lighting, upgraded bathrooms, shade structures, benches, water bottle filling stations, signage, and more spectator seating—a huge upgrade in user experience.

Importantly, the design preserves at least two ADA-accessible courts with wider footprints. As I’ve said before: Coloradans with disabilities are not just spectators. We all want to recreate outdoors, and that means accessibility should be baked into the design—not tacked on afterward.

I appreciate the intentionality here—integrating shade, quieter seating areas for those who may be overwhelmed by noise, and stadium seating that includes wheelchair users at both the top and courtside levels. Even in the photos, I noticed representation: a person with a prosthesis and wheelchair users were included. (Though, I’d love to see active wheelchair users, not just those being pushed.)

Photo credit City of Fort Collins as first design option for Roland Moore Park playground

🛝 Playground Area

Community feedback from the April 2025 open house emphasized shade, nature-inspired play, better sightlines for caregivers, and nearby picnic space. Based on that, the City developed two redesign concepts, each including a bike and skate pump track, climbing elements, shaded areas, and gathering spaces.

But when it comes to accessibility, especially in the playground equipment and surfacing, I don’t think it’s being prioritized enough.

Fort Collins has a few standout accessible playgrounds, but we need to make every new design more inclusive. That means:

Play structures that kids with wheelchairs can access beyond just the ground level

A firm, stable surface confirmed for the entire play area

Thoughtful transition spaces so adults or children with assistive devices can join in sand play

An adult changing table in the restroom

Hooks near toilets for medical bags or equipment

Tables, gates, signage, fountains, and more that follow Forest Service Outdoor Recreation Accessibility Guidelines (FSORAG)

We need true integration, not separation.

Current playground surface at Roland Moore that is inaccessible for wheelchair users

📣 Get Involved: Survey Closes August 15

The City hosted an open house on April 24 and is collecting public feedback through an online survey open until 5 p.m. on Friday, August 15, 2025. If you haven’t submitted your thoughts yet, now’s the time.

It’s not just a chance—it’s a responsibility.

Your input can shape how inclusive these spaces really are. The City is making a commitment to accessibility, but it’s on us to show them what that looks like in the real world.

Don't leave it to chance. Submit your feedback and help build public spaces that reflect our whole community—for this generation and the next.

Protesting for change - closed captioning edition

Hi, I’m Lauren Ash, and I am the new marketing intern here at EBO consulting! I took this job originally with the focus on building my marketing experience, but it has given me so much more than that. It has opened my eyes to the needs of the disabled community. I'm constantly learning about accessibility and how I can make an impact on my community so that it is more inclusive for everyone. And in that spirit, I am taking over this blog today to discuss something I’ve recently learned recently through a podcast by Radiolab - the origin story of closed captioning.

I’ve never thought much about closed captioning; it was just something always there on my TV whenever I watched something. I never took the time to think about where they came from or what it took to get them on my screen. That changed when I listened to the podcast The Echo in the Machine by Simon Adler, a story about identity, language, and accessibility.

Photo credit from National Deaf Life Museum of Gallaudet students during the protest shouting and signing “Deaf President Now!”

The podcast opens with Greg Leibach, a deaf attorney from Queens, New York. He attended Gallaudet University, the only 100% liberal arts university in the world for deaf and hard-of-hearing students. That alone had caught my attention right away. In 1988, when a hearing president who didn’t know sign language was elected for the university, students became enraged, and I can understand why. I can’t comprehend why a president who didn’t represent the school properly would be elected.

Greg, who at the time was the student body president, became the spokesperson for a powerful yet peaceful protest about the presidency of the university. A week after the protest, a new deaf president was elected, giving the students what they so desperately wanted: someone to properly represent them.

Photo credit National Deaf Life Museum

That protest sparked more than a campus change; it created a movement for accessibility nationwide. By 1990, Congress passed the Decorder Act, requiring TVs to include captioning technology. It eventually led to the Telecommunications Act, ensuring that broadcast television was captioned for everyone.

Before then, watching TV without hearing meant relying on a bulky decoder box installed in your home, which was expensive and uncommon, sort of like a VCR. Listening to this made me realize how often I have assumed that things are accessible, simply because they are to me.

Photo Credit from Amberscript

The second half of this podcast dives deeply into the technical aspects of creating closed captions. I assumed that today, most of the captioning has been done by AI, but listening to this podcast, I realized that I was wrong. Up until recently, closed captioning was generated by highly trained steno writers, not just AI. By 2003, it became apparent there weren’t enough steno writers available with the amount of content out there. That's where Meredith Pither, the now president of the National Captioning Institute, came in and was tasked with experimenting with something called a Black Box, a speech recognition box. Faced with unreliable speech recognition, she began “voice writing,” echoing each word for TV into the machine. When that didn’t work, she ended up inventing her own language of code words that the software could understand. Her dedication to making technology accessible is nothing short of inspiring.

This story opened my eyes, not just to how captions came to be, but for every person who fought for access, equity, and proper representation.

Listen here to hear the whole story HERE and let us know what you learned!

Let’s Talk about Bathrooms

Everybody poops. Not glamorous, but important—especially if you’re someone who needs more than just a wide stall to safely and comfortably take care of business.

A lot of places proudly claim their restrooms are “ADA compliant.” Great! But here's the thing: ADA is just the starting line. It’s the legal minimum, not a gold standard. If you've ever used a so-called accessible bathroom that felt like an afterthought, you know exactly what I mean.

So what does it look like when someone designs a bathroom with real people in mind? Here are the features that go beyond the bare minimum and make a bathroom truly inclusive—for more bodies, more needs, and more dignity.

Toilet has a drop bar to assist with standing up from toilet but the sink does not have toe or knee clearance for use of someone with a wheelchair

L-Shaped Grab Bars: Real Support, Real Stability

Most bathrooms stick a horizontal grab bar next to the toilet and call it a day. But L-shaped grab bars give you way more options for support—especially when standing up or shifting side to side. I have had multiple patients that prefer to stack their hands more like using a transfer pole than a horizontal bar. It’s a small upgrade that adds a huge sense of safety and independence.

Adult-Sized Changing Tables

There are many reasons that adults may need a flat surface for hygiene and bowel/bladder management. For example, some people with spinal cord injuries have neurogenic bladder and may need to lay down to empty their bladder or may have aged into an inability to safely stand. And of course, kids with disabilities who did not develop the ability to control their bowel and bladder grow up to adults with disabilities. You’d be surprised how many “accessible” bathrooms don’t have a single place to help an adult with personal care. People end up using the floor of a PUBLIC BATHROOM. If they are lucky they can sometimes use a table or the back of their car but that is a huge problem for privacy. A height-adjustable adult-sized changing table isn’t just about comfort—it’s about respect, hygiene, and basic human dignity. People need care throughout life. Let’s design like that matters.

Image from Julie Sawchuk of Sawchuk Accessible Solutions newsletter

Hooks, Shelves, and a Place to Put Stuff

Try hanging your coat or bag when the hook’s over your head—or worse, there isn’t one at all. Low hooks and small shelves within arm’s reach make a big difference. They’re easy to add, easy to use, and show you actually thought about the person using the space, not just the code.

Showers Designed for Real Use

If there’s a shower in your bathroom, make sure it’s actually usable for a seated or rolling user—not just technically “accessible.” That means a true roll-in entry with no lip, a sturdy seat with a backrest (no flimsy flip-downs that feel like they’ll collapse), and a hand-held showerhead mounted low to start—so someone seated can reach it without standing or stretching.

Also: place the soap, shampoo, and conditioner shelves in front of the seat, not off to the side, on the far wall, or above shoulder height. It’s about designing for comfort and independence, not just compliance. A well-designed accessible shower gives people control over their own bathing experience, safely and with dignity.

Example of accessible shower with a wet room style from Architecture and Access

Sensory-Friendly Lighting and Smells

Good lighting does more than help people see—it creates a space that feels safe and comfortable. Avoid harsh fluorescent lights that flicker or buzz, which can be overwhelming for people with sensory processing disabilities, migraines, or low vision. Choose even, soft lighting with minimal glare.

Strong chemical smells from cleaning products or air fresheners can also be a barrier. For people with asthma, chemical sensitivities, or who use AAC devices (which may rely on breathing support), even a mildly scented soap can make a space unusable. Fragrance-free, hypoallergenic products and regular ventilation go a long way in making restrooms welcoming to more people.

Space for Two (Because Independence Looks Different for Everyone)

Many people don’t go to the bathroom alone—they go with a caregiver, support person, or friend. That means enough room for two people and mobility equipment to move comfortably. A toilet with clearance for a person on both sides, doors that open outward, and enough turning space are examples of thoughtful design. Especially when talking about the shower - shower doors that swing in can really block access. Sometimes a shower curtain in enough.

Bottom line

If we’re only building to meet ADA minimums, we’re not doing enough. Those guidelines are important, but they don’t reflect the full range of needs people have in public spaces. Real accessibility happens when we design with actual people in mind—not just a checklist or code book.

Bathrooms should be places where people can take care of themselves with as much independence and dignity as possible. That means thinking about things like adult-sized changing tables, hooks within reach, and roll-in showers that are actually usable. It means paying attention to lighting that doesn’t overwhelm people and avoiding strong chemical smells that can make the space completely off-limits for others.

This isn’t about adding fancy features—it’s about making sure more people can safely, comfortably, and confidently show up in public spaces. When we design that way, everyone benefits.

What important features of accessible bathrooms did I miss? Contact Me and let me know!

Getting Outside, No Matter What: Exploring Accessibility at Colorado Youth Outdoors and Outdoor Buddies

While doing my bike training, I often take Kechter Road over I-25 into Windsor to ride the country roads. Every time, I pass the Colorado Youth Outdoors (CYO) campus—seeing ponds, trails, and open space—and I always wonder: what goes on there? Recently, I finally got my butt out there to find out. Thanks to a guided tour with Courtney Strouse, Program Director at CYO, and Larry Sanford, President of Outdoor Buddies, I learned just how much this place is doing to make the outdoors more accessible and welcoming for all.

Tucked into the eastern edge of Fort Collins, the 240-acre CYO campus is built to bring people together through outdoor recreation. But what really sets it apart is the intentional effort to make sure people of all abilities can participate. Their partnership with Outdoor Buddies, a nonprofit that connects individuals with disabilities and veterans to outdoor opportunities, is a standout example of inclusive programming in action.

Collaboration That Works

This partnership works because both organizations are rooted in the belief that the outdoors belongs to everyone. Larry and Courtney don’t just talk about access—they make it happen. Whether it’s coordinating volunteers, sharing equipment, or teaming up on sponsorships to improve the fishing pond, their collaboration is full of “we can figure that out” energy.

Outdoor Buddies uses the CYO site to host its adaptive skeet shooting, archery, and fishing programs. At the same time, CYO gains access to Outdoor Buddies’ knowledge and adaptive gear so any youth, regardless of ability, can participate in all CYO programming. Watching them interact on our ride-along, it was obvious they’re committed to each other’s missions and building something sustainable—together.

Image credit from Outdoor Buddies

Adaptive Equipment That Opens Doors

Let’s talk about the gear—because it’s amazing. Outdoor Buddies brings in a wide range of adaptive devices that allow people with mobility limitations to fully participate. One of their most unique tools is the Go-Getter, an ATV-style ride that helps participants get across rough terrain safely. It’s used everywhere from fishing docks to pronghorn hunts in Colorado and Wyoming.

They also offer ActionTrack chairs, which are track-driven, all-terrain mobility devices. These let people using wheelchairs navigate dirt, grass, and even trails covered in mulch. They’ve even built an immersive fly-fishing bridge this year that lets you “walk on water”—I’m not kidding, it’s impressive (see photo).

For shooting sports, they provide adaptive gun rests, sip-and-puff trigger systems, and other supports that allow safe use from seated positions. Archery includes modified bows and hands-free aiming systems. Fishing setups include electric reels and grip supports—there’s a solution for just about everything.

Check It Out Yourself!

I finally got to see it all in action at Outdoor Buddies’ Family Day at Swift Ponds, which just took place this past Saturday, June 7. As usual, I biked over there with a friend for training. Family days typically occur in the Spring and Fall at the CYO campus and are full of adaptive fishing, BB-gun and trap shooting, archery, and even a catch-clean-cook experience (yes, people were grilling rainbow trout they caught right there).

Everything is designed for access—wheelchair-accessible fishing docks, five trap houses, and a whole fleet of mobility devices such as track chairs and the Go-Getter. Whether you came to learn a new skill or just be outside with your family, there was something for you.

Trained volunteers are there to help with setup, modifications, and encouragement. The vibe is simple: show up as you are, and we’ll make it work. As Larry puts it, “I will get anyone outside no matter what. We will make it happen.” And honestly, what can’t be solved with duct tape, zip ties, and a bungee cord?

Get Moving

If you’ve ever felt unsure about whether the outdoors is really for you—or for someone you care about—this partnership shows that with the right people, the right equipment, and a little creativity, there are no barriers that can’t be worked around. Whether you’re catching your first fish, rolling a track chair up to the archery line, or just enjoying the quiet of the pond trail, Colorado Youth Outdoors and Outdoor Buddies are proving that everyone deserves a place outside. If you are interested in joining a program please contact Outdoor Buddies HERE. If you are looking to donate you can donate to Colorado Youth Outdoors or Outdoor Buddies to continue this great work. Look out for me on the road waving to you on the pond!

Why We Need to Speak Up for Public Lands—Now More Than Ever

If you care about access to the outdoors—for recreation, reflection, or healing—it’s time to pay attention to what’s happening in Congress. Right now, several bills threaten the future of our public lands, while others offer hope. And the difference between whether they pass or not comes down to people like us showing up, speaking out, and reminding our representatives that public land belongs to the public.

Three recent bills raise red flags for anyone who values shared access to natural spaces:

The Ending Presidential Overreach on Public Lands Act would limit a president’s ability to designate national monuments under the Antiquities Act. That sounds like a check on executive power, but in reality, it undercuts one of the few tools used to protect culturally and ecologically important landscapes—especially when Congress drags its feet.

Then there’s the Productive Public Lands Act, which aims to prioritize extractive uses like logging and grazing. It’s framed as a way to make public lands “work for us,” but let’s be clear: it redefines productivity in terms of short-term profit, not long-term public benefit.

The Mining Regulatory Clarity Act is another dangerous one. It gives mining companies even more access and fewer restrictions, making it easier for them to exploit land that should be protected. This bill would weaken existing safeguards and make it harder for land agencies to deny mining claims—even in sensitive ecosystems or near recreation areas.

But here’s the thing: public pressure can make a difference. A powerful example came recently in Nevada, where a proposal in the House reconciliation bill would have allowed thousands of acres of public land to be sold off for development. People across the country raised their voices—individuals, advocacy groups, and local communities. That vocal opposition led to the provision being removed. It’s proof that when we speak up, we can stop bad policy in its tracks.

There are also good bills out there that deserve our support. The Keep Public Lands in Public Hands Act is straightforward—it would block efforts to transfer public land to private or state ownership. The Protect Our Parks and Save Our Forests Act strengthens protections for urban parks and old-growth forests—two critical areas for climate resilience and equitable access.

Public lands aren’t just for sightseeing or backpacking. For people with disabilities, they’re vital places for independence, connection, and well-being. But that only works if those lands are protected and thoughtfully managed. If areas are sold off or handed over to private interests, accessibility efforts stall. There’s no trailhead to improve, no beach to make wheelchair-accessible, no boardwalk to maintain—because the land is gone.

The bottom line? Public lands are under threat, but they’re also a source of incredible possibility—if we fight for them. Call your representatives. Share about these bills with your communities. Support organizations that defend access and conservation. We can’t take these places for granted.

Because once land is sold or stripped, we don’t get it back.

Colorado’s Outdoors Are for Everyone—Let’s Make Sure They Stay That Way

If you’ve spent any time outside in Colorado, you know how special it is here. From winding trails through the pines to quiet fishing spots and open spaces full of wildlife, there’s something for everyone—or at least, that’s the goal.

Back in 2015, Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW) adopted a 10-year strategic plan that laid out their priorities through 2025. One of the big takeaways from that plan was a clear commitment to making outdoor spaces more accessible. That means not just protecting the land and wildlife, but making sure that people of all abilities can enjoy the outdoors in meaningful ways.

The plan called for more accessible and inclusive recreation opportunities across the state. It emphasized improving infrastructure, offering programs that welcome a wide range of people, and taking a hard look at what barriers might be keeping some folks from participating. In short, it wasn’t just about checking a box—it was about real access and inclusion.

And we’ve seen progress. Many state parks now have accessible trails, fishing piers, and campsites. Some, like Staunton State Park, even have track chairs available for visitors who use wheelchairs, opening up parts of the park that were once totally out of reach. You can read more about Staunton State Park and their climbing opportunities on a previous blog HERE. Interpretive programs are starting to offer sensory-friendly options or adaptive gear, and more parks are being designed with universal access in mind from the start.

That said, there’s still work to do. Not every park or program is truly usable for everyone, and physical access is only part of the picture. Making outdoor spaces truly welcoming means listening to the people who use—or want to use—those spaces and learning what’s working and what’s not.

That’s where you come in.

CPW is working on its next 10-year strategic plan, and they’re asking for community input. This is your chance to speak up about what’s important to you, especially if you’ve experienced barriers in the outdoors or work with communities that do. Whether it’s better signage, more accessible trailheads, inclusive programming, or simply being seen and heard in decision-making, your perspective matters.

Colorado’s parks and wild places are for all of us. Let’s make sure the next decade reflects that.

Want to weigh in? Visit the CPW website for the community feedback form for the next strategic plan. It only takes a few minutes—and your voice could help shape the future of outdoor recreation in Colorado. Contact me if you have any questions on the form!

Accessible Bathroom Design in Outdoor Developed Areas: What Really Matters

Let’s talk about bathrooms. Not the most glamorous part of outdoor recreation planning, but absolutely one of the most essential—especially when we’re talking about accessibility. Whether it’s a busy trailhead, a lakeside picnic area, or a remote camping spot, having an accessible bathroom can be the difference between someone enjoying the outdoors or staying home.

What the Guidelines Say

The Outdoor Developed Areas Accessibility Guidelines from the U.S. Access Board were created specifically to help land managers design spaces that actually work for everyone—including people with disabilities. These guidelines apply to places like campgrounds, picnic areas, and trails on federal land, and they’re quickly becoming the go-to reference even beyond federal sites.

For bathrooms, the big takeaways are about accessible routes, maneuvering space, and clear floor space. Paths to the restroom need to be firm, stable, and slip-resistant. The entrance should have at least a 32-inch clear width, with enough space inside for someone using a mobility device to turn around—a 60-inch turning diameter is the standard. The Americans with Disabilities Act has further specifications in bathrooms to help guide you.

Even in vault toilets or primitive restrooms, the goal is the same: a space that a person can get to, get into, and actually use without needing help.

Image credit from Backpacker Magazine

The Real-World Usability Layer

Meeting guidelines is one thing, but designing for real-life usability is where we make the biggest impact. Here's where experience and feedback from actual users comes in:

Adult-sized changing tables: These are a game-changer for people with complex disabilities and caregivers. Most public bathrooms only have baby changing stations (if that), which don’t meet the needs of older kids or adults. Adding a full-size, height-adjustable changing table makes outdoor spaces more inclusive for everyone.

Sinks with knee clearance: Often, sinks are placed at a height or depth that makes them basically unusable for someone in a wheelchair. Providing clearance underneath and easy-to-use faucets (think levers or motion sensors) can make a big difference.

Shelves and hooks: It sounds small, but it’s not. Having a shelf at the right height lets someone set down personal items by the toilet without juggling or putting them on the floor. This can be essential when you are needing to self catheterize to use the toilet or if you need extra supplies for any reason. Multiple hooks at different levels help everyone—from kids to people using mobility devices—store things where they can reach them.

Grab bars: These are required, but placement matters. It’s worth going beyond the bare minimum here—talk to users, especially those with disabilities, to make sure the layout makes sense and truly supports independence.

Why It All Matters

At the end of the day, accessibility isn’t just about checkboxes—it’s about dignity, independence, and inclusion. Bathrooms might not be the highlight of someone’s outdoor experience, but when they’re poorly designed, they become a barrier. And when they’re done right? They quietly enable more people to enjoy nature, explore new places, and feel welcome.

If you’re planning a new recreation site or upgrading an old one, think about who’s not showing up—and whether a better bathroom design could be part of the solution.

Accessibility Audit at Overland Park

It was a beautiful day to be outside, and my two pups were loving every minute of it—soaking up the sunshine and sniffing everything in sight. We wandered along the paved and crusher fine trails, through the grassy field, and around the different facilities, including a basketball court, tennis court, and baseball field. In total, it took us about 30 minutes to walk the park and assess its accessibility. That’s how quick and easy it is to use the Mobility Assessment Tool once you’re trained and familiar with it.

This powerful tool was designed by people with disabilities in partnership with Fort Collins Natural Areas to go beyond just meeting ADA regulations and really capture usability and potential barriers. It’s all about understanding how people actually experience the space. Let me walk you through how it works.

The accessibility tool is divided into four categories: Parking, Signs and Features, Facilities, and Trails. Each category has a list of requirements related to accessibility, and each requirement gets a rating from 0 to 5.

Image from training completed with Larimer County Natural Resources

For example, in the Parking section, the first requirement is “Dedicated number of accessible parking spaces.” The possible answers range from “Unclear or no parking spaces,” which would get a score of 0, to “Lots of ADA and accessible parking, some large ramp size,” which would get a score of 5. The goal is to aim for scores of 3 or higher, showing moderate to high evidence of accessibility for that requirement.

You might notice that some of the requirements in this tool are subjective. For example, what does “lots of ADA and accessible parking” really mean? That’s intentional because the goal of this tool isn’t just to meet the bare minimum standards set by the ADA. It’s not about simply checking a box to say there’s one ADA spot for every 25 parking spaces. Yes, it’s important to meet legal requirements, but accessibility goes beyond compliance.

When we talk about these subjective categories, what we’re really asking is: How welcoming is your space for people with disabilities? If you’re aiming to make your park or trail system a place where people of all abilities feel encouraged to visit and participate, your parking should reflect that. That might mean having more accessible parking spots than the minimum required by law. It’s about creating a space that’s genuinely usable and inviting for everyone.

Dog poop bags on uneven surface and quite high up making access challenging for a seated wheelchair user

I’ve used this tool a bunch of times, so I know the rhythm and requirements well enough to move through it pretty quickly. As I go, I take photos of spots that seem like they could use some improvements or might be tricky for accessibility—like the doggy bags that are just a bit too high or someone seated (pictured above), or the drop-off that could use some maintenance (pictured below).

Right now, Jim and I are working on making the tool available online so you can upload all your pictures and scores in one place as you go. It’ll make the whole process a lot more efficient!

Gap from run off between sitting area and basketball court making access more challenging. Recommending maintenance for fill in and/or plans for managing water run off

Now for the scoring. Overland Park ended up with a lower-than-expected average accessibility score of 0.5 across all categories. Part of that is due to some temporary factors—like ongoing construction affecting parking and the bathrooms being closed for the winter. Without these seasonal changes, the score could improve by 1-2 points.

That said, there are some great features worth highlighting! The trail has a welcoming grade with beautiful views of the ponds, and there are benches along the way, making it a nice spot to pause and take in the scenery. Although the crusher fine section is a bit soft for most wheelchairs, the overall experience is pleasant, and the grade toward the pond is about 5%—steep but doable if you’re looking to fish.

One area that could use some attention is the path to the baseball field stand, which is currently grassy and uneven. Making this route smoother would really help improve accessibility and usability.

Jim Mull testing the accessibility to reach dog bags at Lions Park Open Space

Bottom line, The Mobility Assessment Tool is a game-changer for looking at accessibility from the perspective of someone with a disability. It goes beyond just meeting ADA requirements and actually focuses on how usable a space is. Once you’re familiar with it, the tool is quick and easy to use and works great for all kinds of open spaces—like parks, trails, and recreation areas. It really helps pinpoint practical changes that make outdoor spaces more welcoming and accessible for everyone. Contact Me if you are interested in learning more for a free 20 min tutorial on the tool!

Disability Rights at Risk - Lawsuit against section 504

Has anyone else felt overwhelmed by the sheer number of policy changes in the past few months? With so much happening, it’s easy to miss the quieter battles taking place behind the scenes. One of those battles—one that could have devastating consequences for disabled people—is Texas v. Becerra, a lawsuit filed by Texas and 17 other states attempting to dismantle Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act.

Texas vs. Becerra

Back in September 2024, Texas and 17 other states sued the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) in an effort to declare Section 504 unconstitutional. You may remember me discussing section 504 and the disability rights movement prior in one of my recent blogs HERE. The lawsuit was initially framed as a response to the Biden administration’s decision to include gender dysphoria as a protected condition under Section 504. But here’s the problem: the lawsuit goes far beyond that one rule. It specifically challenges the entire law, including its integration mandate, which prevents disabled people from being forced into separate, unequal services.

If this lawsuit succeeds, it could gut disability protections across education, healthcare, public transportation, and outdoor recreation, allowing states to refuse compliance with Section 504 while still receiving federal funding. To understand how disastrous that would be, we need to step back and look at what Section 504 actually does.

Image Credit from Plain Language Explainer Texas v. Becerra

What Section 504 Does and Why It Matters

When the Rehabilitation Act was passed in 1973, it was the first time in U.S. history that a federal law explicitly banned discrimination against people with disabilities. Section 504 states that any entity receiving federal funds—such as schools, public transportation, and healthcare programs—must provide equal access to people with disabilities.

At its core, Section 504 is about ensuring disabled people aren’t segregated or excluded from society. It was the first federal civil rights law to ban disability-based discrimination, requiring that any program receiving federal funds—schools, hospitals, public transportation, parks, and more—provide equal access to disabled people. It is the beginning of Universal Design principles, focusing on equitable use.

This law isn’t just about paperwork—it changes lives. For example, in education, 1.6 million students had Section 504 plans in the 2020-2021 school year alone, ensuring they had accommodations like extra time on tests, assistive technology, or seating arrangements that met their needs. In healthcare, it mandates access to sign language interpreters, accessible medical information, and telehealth services. Public transportation agencies must provide priority seating and boarding assistance. And for federally funded National Parks, it ensures programming access for people with disabilities, making public lands open to everyone.

A real-world example comes from Mercy Botchway, a student who used a Section 504 plan to access class notes, assistive listening devices, and seating adjustments so she could fully participate in school. Without those accommodations, she said it would have been impossible for her to attend. Stories like hers remind us that Section 504 isn’t just a bureaucratic regulation—it’s a law that allows disabled people to fully engage in their communities.

Image Credit from the New York Times

A Hard Fought History

But Section 504 didn’t come easily. When the Rehabilitation Act passed in 1973, the federal government refused to enforce it for years. In response, disability activists led the 504 Sit-In of 1977, occupying federal buildings for nearly a month until officials finally signed the regulations into law. That victory laid the groundwork for future disability rights protections, including the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in 1990, which expanded access requirements beyond federally funded programs to state and local governments, businesses, and public spaces.

Now, Texas and other states want to roll back that progress.

Transphobia Hurts Everyone

Bottom line, this lawsuit is fueled by transphobia. You can’t get around it. The states pushing it are using harmful, false narratives that portray trans people as dangerous, echoing the same misinformation that has been used to justify discrimination for decades. This wave of anti-trans legislation has shamefully increased over the past few years. But here’s the truth: trans people have always existed and will continue to exist. They have the right to be here, just like everyone else.

And this isn’t just an attack on trans people—it’s an attack on all disabled people. By challenging the very foundation of Section 504, these states are arguing that they should be free to discriminate without consequence. But history shows us that when one group loses rights, everyone’s rights are at risk.

LFG

But let’s get to the good news. The disability community is fighting back against these attacks. They are uniting and pushing hard. Organizations like the National Disability Rights Network and the American Association of People with Disabilities are fighting in court, while activists are mobilizing online and in protests. Social Media Influencers have expanded the reach of this information and are massively spreading the word on the threats to section 504. Thanks to this pressure, the attorneys general of the 17 states have publicly claimed they only want to remove protections for gender dysphoria—but their lawsuit still challenges Section 504 as a whole. No changes have been made to their legal filing to reflect their so-called clarification.

For now, the case has been put on hold until April 2025, when the court will review updates from both sides. But the threat isn’t over. If this lawsuit moves forward, it could undermine decades of progress.

That’s why it’s critical to take action now. If you live in one of these 17 states, contact your attorney general and demand that they withdraw their support from this case. The fight isn’t just about policy—it’s about protecting real people, real rights, and real access. Check HERE for more ways to stay informed and please reach out to your representatives. To borrow the women’s national soccer team phrase, Let’s Fucking Go!

Wilderness Inquiry: Opening the Outdoors for Everyone

I am always looking for organizations that are serving the community well and getting more people outside. So today, I want to shine a spotlight on Wilderness Inquiry (WI). For nearly 50 years, WI has created outdoor experiences where people of all abilities can explore, connect, and discover new possibilities. Through adaptive paddling expeditions, multi-day camping trips, and inclusive programming, WI ensures that nature is open and welcoming for everyone.

How WI Supports Adventurers with Disabilities

When you are doing something new, it is important to trust the organization has thought about accessibility systematically. WI has a structured process for registration that ensures each participant gets the support they need. If you go to their FAQ page and click on Accessibility, they will list out the step by step collaborative procedure to determine that you feel safe and have the equipment you need. I particularly appreciated their discussion on the presence of a support person on the trip, and the pricing that is associated with that registration. Per their policy, “This fee will be based on the base price for the trip, any additional costs associated with the trip support required (e.g., equipment), and our modest administrative fee. For select continental U.S. experiences, the fee may be fully waived for personal care attendants or ASL interpreters.” By having this policy in place, they are establishing credibility with understanding the community and acknowledging the financial burden associated with caregiving. This information and more, including recommendation for a manual wheelchair for trips, can be easily found on their website. Another plus.

Affinity Group Trips: Community Through Shared Experiences

Another element in the plus column for this organization is their programming designed to cater for specific communities. WI’s Gateway to Adventure trips help individuals with cognitive disabilities build confidence in the outdoors. Many later transition into fully integrated trips, proving that outdoor recreation is possible for everyone. WI also offers Deaf, Deafblind, and Hard of Hearing as well as Neurodiverse trips. These trips create space for connection and shared experiences in nature.

Image from Wilderness Inquiry’s “Life Changing Stories”

Testimonials

But more than anything, I want you to hear from the actual participants who have been on these trips. Mark, a visually impaired 37-year-old, has paddled with WI across North America, from the Boundary Waters to Yellowstone Lake and even Alaska’s Porcupine River. His favorite trip? A 750-mile canoe journey through the Arctic Circle.

“What I love most is the camaraderie,” Mark says. “In the wilderness, we’re all the same—we work as a team, rely on each other, and form lasting friendships.” Thanks to WI, he’s planning even bigger adventures, like kayaking in Prince William Sound. “Before WI, I didn’t think trips like this were possible. They’ve opened up the world for me.”

Dave, a veteran and former rugby player, found a new sense of self on a WI trip.

“Before this, I never considered camping on my own,” he said. “Now I know my only limitations are the ones I set for myself.” Inspired by his experience, he’s already taken a solo camping trip.

Image from Wilderness Inquiry’s “Life Changing Stories”

The Outdoors is for Everyone

Wilderness Inquiry isn’t just about organizing trips—it’s about making outdoor adventure possible for more people. Through thoughtful planning, creative problem-solving, and a commitment to inclusion, WI ensures that everyone has a chance to experience the outdoors, build confidence, and find community. Let me know if you have been on a trip from Wilderness Inquiry or a similar organization!

What is the future of accessibility in the US?

The outdoor industry has made some big strides over the last few years to be more inclusive and accessible for people with disabilities. But under a Trump presidency, it’s going to be a lot harder to keep that momentum going. The administration’s push to shut down federal diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility (DEIA) programs could seriously set us back, making it harder to tackle ableism and the broader inequities that keep outdoor spaces inaccessible for so many people.

Specifically I wanted to shed light on two new executive orders called "Ending Radical And Wasteful Government DEI Programs And Preferencing" and “Ending Illegal Discrimination And Restoring Merit-Based Opportunity." These orders paint DEIA work as "radical," "wasteful," and "illegal." They demand detailed records from anyone who’s gotten federal grants or contracts for DEI initiatives, and go further to discourage accessibility work in the private and state sectors, calling for investigations into DEI practices and even threatening them with lawsuits (Sect 4). Unfortunately, this is sounding all too familiar from American history (click here for information on the Red Scare).

This kind of fear-mongering discourages outdoor organizations and state programs from prioritizing inclusion. It could mean fewer adaptive recreation programs, less training on accessibility, and even abandoning projects to make trails and facilities more inclusive. It’s clear the goal is to discourage organizations from doing this kind of work by making it feel risky or controversial. For those of us who have been advocating for accessibility in outdoor spaces, this is a huge step backward.

Let me remind you that 25% of Americans have a disability, making this the largest minority group in the country. This population includes individuals of all ages, backgrounds, socioeconomic statuses, and races. The proposed policies will negatively impact a quarter of our population, including veterans who have served to protect our freedoms—yet are now at risk of being excluded from equitable access to outdoor recreation.

While these executive orders don’t repeal the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) or the Architectural Barriers Act (ABA), we all know these laws don’t go far enough. They fail to allow for full participation in society and come with serious limitations, including lack of regulations for outdoor spaces, which is exactly what we’re trying to expose and fix with accessibility work. Relying solely on these limited frameworks leaves huge gaps in equity and access—gaps that federal DEIA initiatives were starting to address before they were gutted. Accessibility work is fundamentally a civil rights effort aimed at ensuring equal access, opportunity, and dignity for disabled individuals in all aspects of society, including public spaces, services, and recreation. This work is far from “wasteful.”

I also urge you to understand that accessibility and equity go hand in hand; there is real intersectionality here. We cannot have progress making places more approachable for people of all abilities without the key work that is being done for Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities. Not to mention that BIPOC people experience higher rates of disability because of systemic barriers in healthcare, housing, and employment. When racial equity takes a hit, accessibility does too. Ignoring this intersection only deepens existing barriers.

So where do we go from here? First, we need to keep fighting for policies that prioritize accessibility and equity. That means pushing back against efforts to dismantle DEIA programs and making sure disabled voices—especially from marginalized communities—are front and center. Find your local community organization and work to collaborate to keep accessibility on the agenda. Second, there are a lot of people who have been doing this work for the last 4 years who have lost their jobs and/or partners related to this order. Step up and take their training online, join their Patreon, etc. Lastly, contact your representatives in congress about your needs related to accessibility and the importance to go beyond ADA and ABA requirements for true equity. They need to hear it from you, their constituents, to understand your lived experience. Outdoor organizations also have a role to play. Even in this tough political climate, they need to stay committed to creating inclusive and accessible spaces. By standing firm, they can ensure that outdoor spaces remain places where everyone—no matter their ability or background—can feel welcome and included.

Image credit from the New York Times

While this is a scary time, it’s also an opportunity to come together and strengthen our resolve. Let me remind you that the ADA itself was created because people with disabilities stood up against a federal government that wasn’t recognizing their needs. And it started small in local spaces and grew toward this major legislation. We’ve been here before, and we know what to do—stand together, raise our voices, and demand the changes we deserve.

Disabled Hikers: Using the Spoon Theory to Make Trails More Accessible

I wanted to shed some light on an amazing organization out of my hometown, Seattle, WA called Disabled Hikers. They’ve been doing incredible work to make the outdoors more inclusive for people with disabilities, and their approach is something I’ve found invaluable in my work. What sets them apart is that they are an entirely disabled-led organization committed to justice, access, and inclusion. They have worked with Washington State Parks Foundation, Justice Outside, Land Trust Alliance, and much more. In particular, I love their use of The Spoon Theory in their trail difficulty guides, providing a thoughtful and practical way to help people manage their energy while navigating the great outdoors.

Image from Disabled Hikers Guidebook page

What Is The Spoon Theory?

The Spoon Theory is a concept that explains how people with chronic illnesses or disabilities manage their limited energy. Each “spoon” represents a unit of energy, and for people with conditions like chronic fatigue or mobility impairments, the number of spoons they have each day is finite. Completing everyday tasks—getting out of bed, making a meal, or getting dressed—uses up spoons. The idea is that someone without a chronic illness may have a nearly unlimited supply of spoons, but someone with a disability needs to conserve them wisely throughout the day.